Daidokoro Monogatari: Stories of the Japanese house from the kitchen

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.20868/cpa.2021.11.4829Parole chiave:

Domestic space, House design, Kitchen, Gender, Japanese architectureAbstract

Abstract

Telling a story (monogatari) about the Japanese kitchen inevitably entails reflecting on the most celebrated architectural typology in the country, the detached house. After World War II, it became the basic unit that shaped the Japanese urban landscape. Rapid economic growth resulted in a clear pattern not only in the housing market but also in family composition. Influenced by western models, conventional gender roles were embodied in the breadwinner (salaryman), related to corporate centers, and the full-time homemaker (sengyō shufu), associated with the domestic space. Among all the rooms, the kitchen was the clearest in its premise: the place where the wife cooks. This gender construct was encoded in its spatial articulation, with the kitchen being hidden from the rest of the house and usually occupying a dead-end position. Japanese architects have challenged these conventions through radical house designs, often praised for their smallness, whiteness, and lightness. However, it is necessary to go beyond this ‘fetishization’ to evaluate these proposals for the relationships they pose. Their bold designs are not only ground-breaking in formal terms but go further, subverting normative notions of domesticity and suggesting alternative gender ‘performativities’ in architecture. The kitchen is often the site of the most outstanding experimentation, materializing inventive concepts of living. Questions concerning technology, economy, and above all, gender unfold in this domestic workplace. If connected or isolated, visible or hidden, it materializes power relations through architectural actions. From a critical gender perspective, this article takes Japanese houses from the 20th century to the present day, showing diverse strategies and exposing those architectural principles and social conventions against which they rebel. These houses foster the creation of alternative realities, disrupting preconceived ideas of what is a kitchen, what is a house, or what is a family

Downloads

Riferimenti bibliografici

Arango Flórez, John y Natalia Pérez Orrego. "Espacios desde objetos. Relaciones entre modos de vida y arquitectura a través de muebles". Iconofacto 12, no.19 (2016): 170-194.

Atelier Bow-Wow. “House Genealogy, Atelier Bow- Wow: All 42 Houses”, Japan Architect 85 (Spring 2012): 114.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Nueva York: Routdlege, 1990.

Colomina, Beatriz. “The Split Wall: Domestic Vouyerism”. En Sexuality and Space, edited by Beatriz Colomina.73-80. Nueva York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992.

Diller, Elizabeth. “Bad Press”. En Gender, Space and Architecture, eds.Iain Borden, Barbara Penner and Jane Rendell. 12. Londres: Routledge, 2000.

Gómez Lobo, Noemí. “Two Houses and Two Women Challenging Domesticity in Modern Japan”, enThe 16th International DOCOMOMO Conference Tokyo Japan 2020+1 Proceedings, eds. Ana Tostões and Yoshiyuki Yamana. 1498-1503. Tokyo: DOCOMOMO, 2021.

Hamaguchi, Miho. The Feudalism of Japanese Houses (Nihon jūtaku no hōkensei). Tokio: Sagami Shobo, 1949.

Hayashi, Masako. “My architectural method – Excerpts from a lecture”. En Masako Hayashi (Modern Architect). 10-12. Tokio: SD Kajima Publishing, 1981.

Hirai, Kiyosi. The Japanese House Then and Now. Tokio: Ichigaya Publications, 1998.

Ito, Toyo. Toyo Ito Architecture 1971-2001. Tokio: Toto, 2013.

Kitagawa, Keiko. Dining Kitchen wa Koushite Tanjoshita: Josei Kenchikuka Miho Hamaguchi ga Mesashita mono (The process of Dining-Kitchen: What Miho Hamaguchi, the First Architect, Aimed at). Tokyo: GihōdōShuppan, 2002.

Nakagawa, Takeshi. La casa japonesa: espacio, memoria, y lenguaje. Barcelona: Reverté, 2016.

Ogawa, Nobuko and Atsuko Tanaka. Big Little Nobu: Wright'sdisciple and female architect Nobuko Tsuchiura (Biggu, ritoru, Nobu: Raito no deshi, joseikenchikuka Tsuchiura Nobuko). Tokyo: Domesu Shuppan, 2001.

Sand, Jordan. House and Home in Modern Japan: Architecture, Domestic Space and Bourgeois Culture, 1880-1930. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Tsukamoto, Yoshiharu. “Family Critiques.” En The Japanese House: Architecture and Life after 1945.37. Tokio: Shinkenchiku-sha, 2017.

Ueno, Chizuko. The modern family in Japan. Its rise and fall. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2009.

Dowloads

Pubblicato

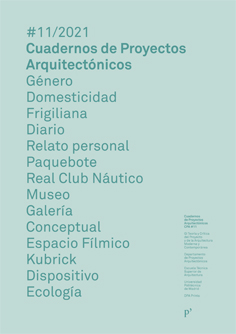

Fascicolo

Sezione

Licenza

1. Los autores conservan los derechos de autor y garantizan a la revista el derecho de una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional que permite a otros compartir el trabajo con un reconocimiento de la autoría.

2. Los autores pueden establecer por separado acuerdos adicionales para la distribución no exclusiva de la versión de la obra publicada en la revista (por ejemplo, situarlo en un repositorio institucional o publicarlo en un libro).